Yoga can improve sleep for cancer survivors, study says

Islamabad, November 8 (Newswire): Yoga classes can help cancer survivors sleep better, according to a study.

Two-thirds of cancer survivors have trouble sleeping, even two years after they’ve finished chemotherapy or radiation. Even more report persistent fatigue, says study author Karen Mustian of the University of Rochester Cancer Center, whose findings will be formally presented in June at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting in Chicago. Note:

The National Institutes of Health, which funded this study, has funded a number of studies to scientifically evaluate complementary approaches to cancer. In recent years, for example, scientists at the oncology meeting have reported that ginger alleviates chemo-related nausea, gingko relieves cancer-related fatigue, but that shark cartilage has no effect on lung cancer. Americans spend $34 million out-of-pocket each year on alternative or complementary approaches, according to a 2009 analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many researchers are in interested in yoga, as well. The University of Kansas Hospital is launching a study on the effects of yoga on atrial fibrillation, which can be triggered by stress.

Doctors don’t know exactly why sleep problems are so common after cancer therapy, Mustian says. But she notes that some chemotherapy can damage cardiac muscle, leading to heart failure many years after treatment. It’s possible that fatigue could be an early warning sign of heart damage, Mustian says.

Mustian says she was drawn to yoga because it’s safe, non-invasive and involves no medication. And small, preliminary studies have suggested that it can improve sleep.

In her experiment, yoga didn’t replace conventional therapy, such as surgery and radiation.

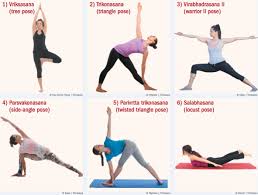

Researchers randomly assigned 410 people who had finished treatment to receive either their usual follow-up care or attend a 75-minute yoga class, twice a week, for four weeks. The classes included breathing exercises, meditation and postures used in the hatha and restorative schools of yoga, Mustian says. Patients had an average age of 54. About 75% had been treated for breast cancer.

After four weeks, cancer survivors who attended the specially designed yoga classes also were less fatigued and sleepy during the day than others, Mustian says. They rated their quality of life more highly than those who didn’t take yoga, and they used fewer sleeping pills.

Because her classes used specific types of yoga, Mustian says she doesn’t know if other forms of yoga — such as more aerobic versions or classes held in a very hot room — would also be safe or effective for cancer survivors.

Mustian’s study will likely encourage many cancer survivors and doctors to try yoga for sleep problems, says Priscilla Furth, a professor at Georgetown’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

But Douglas Blayney, president of the oncology society, says the study doesn’t reveal which parts of the yoga course was most beneficial. Participants could have been helped by a combination of exercise, meditation and the social support provided by meeting with fellow survivors, he says.

Mustian says it’s possible that yoga helped cancer survivors reduced anxiety and helped patients relax, lowering levels of stress hormones.