Michael X: The multiple lives of the man once dubbed the UK’s answer to Malcolm X

London: When police in Trinidad showed up to investigate at the scene of a burned down commune in 1972, they quickly realised they were looking at the work of seasoned criminals.

As far from an open and shut case of arson as was possible to imagine – what emerged from the scene would be even more sordid – and ultimately end the life of one of Britain’s most notable black activists.

Concealed within the burned-down ruins within a shallow grave was the body of Joe Skerritt. His throat had been slashed.

In another hole the remains of a young woman – Gale Benson. She’d been stabbed multiple times with a cutlass before being buried alive.

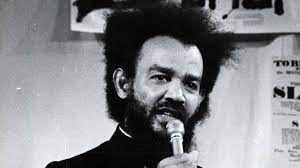

The property had been rented to Michael de Freitas, otherwise known as Michael Abdul Malik, and then Michael X, an activist, hustler and community leader who’d made his name in the UK during 1960s as the figure at the forefront of the country’s Black Power movement.

The commune had attracted the likes of John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Muhammed Ali as visitors, well before the murders.

He would subsequently be charged with two murders, put on trial for one, and then hanged in Trinidad, the country where he was brought up.

His trial heard the two victims were residents of the commune, murdered at his instruction by two of his followers because he wanted “blood”.

It was the act of somebody who had shown a predilection for violence and confrontation while building his reputation as an activist in London.

De Freitas’s journey, as part of the Windrush generation, took him from roles as varied as campaigner, to a friend of A-list celebrities such as Lennon and Ali, to a criminal monitored by MI5 and wanted by Interpol.

Such notoriety ought to put his name at the forefront of British black history. But he is arguably unknown here when compared to prominent black US figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X.

Dhanveer Bhar, a lecturer in Black British History at the University of Leeds, says de Freitas was a “deeply flawed” but “necessary figure” in the UK and said there is little comparison between his country and the US when it comes to racial politics and the people who represented the countries’ respective civil rights movements.

“To compare the politics of black radicalism in the US and UK during the 1960s does not really tell us a great deal,” he said. “In the US you had a black population who had been a presence in the country for hundreds of years since enslavement, and over that time developed alternative institutions and organisations to combat the racism soaked into the soil of America.

“So, US black radicalism in the 1960s was an expression of a history which had been organic to the North American land mass for some time, even if what made it organic was its resistance and opposition to the American project.

“Although there had been a black presence in Britain for centuries, the work of Ron Ramdin and Peter Fryer tells us this, it was not on the same scale in terms of pure numbers on the land mass,” he added.

Born in Port au Prince in Trinidad, De Freitas moved to London in 1957 as a young adult following a spell working as a ship seaman. With little money on his arrival in the capital, having been restricted to low-age menial jobs, it appears he turned to hustling and crime.

According to the Who Was Michael X podcast, produced by Hamza Salmi, like many in the Windrush generation brought over to rebuild the country after the Second World War, de Freitas came armed with his British passport and with an expectation he would be welcomed. The opposite was the case.

Mr Bhar said: “Britain’s centuries-long contact with black people had been imposed through both slavery and colonisation and therefore, for the most part, those populations had remained ‘out there’ in the Empire.

“It was only after the end of the Second World War, after Britain’s call out to its imperial subjects to come and rebuild a broken country, that a significant and settled black presence becomes part of the social fabric.

“In a way, the 1960s is when modern Black British politics and culture began to develop. And that development involved bringing over and adapting political ideas and cultural forms which had been assembled ‘back home’ in the colonies as part of a longer continuum of resistance to empire.”

So it was an embittered and resentful de Freitas who stood up and spoke at a meeting in August 1958 aimed at mobilising the black community against racist attacks. He was encouraged at the meeting, according to Mr Salmi, to take a more active role in the Notting Hill riots of August 1958.

It was in this period de Freitas is reported to have explored hustling and racketeering, evicting people from their homes for non-payment of rent. He was jailed for stealing paint while on a ship and his marriage broke down. But, a new relationship with a liberal white woman, which started after his release, would immerse him in the world of 1960s counterculture.

These new connections would lead him to a chance meeting with Malcolm X during his visit to the UK in 1965. The pair went on a joint trip to Smethwick at a time when the local council had plans to segregate. According to Who Was Micahel X, it was here the US activist told an impressed De Freitas that the black community needed to stand alone.

Mr Bhar said de Freitas’s “political conversion through meeting Malcolm X” was what stood out most about him, as well as his change of name to Michael Abdul Malik when he converted to Islam.

The beginning of the end of his time in the UK came after he set up the Black House complex in Holloway Road in 1969 with his wife Desiree, with the support of Lennon, Sammy Davis Jr, comedian Dick Gregory and Nigel Samuel, who was the son of a property developer.

It was a youth centre for young black men, with a games room, self-defence classes and an office for de Freitas too.

But in 1970, that office was the scene of a disturbing moment, when a man in a pay dispute with a young black cleaner was invited in by de Freitas, forced to wear a collar and paraded around the room before being ordered to pay for a signed copy of his autobiography.

Police raided the property as a result and arrested de Freitas. He was then charged with robbery and at this point – facing jail again – made plans to leave the country after declaring Black Power movements were no longer needed in the UK.

Within weeks of handing over his mini-empire – it was looted and burned down, and Michael X had returned to Trinidad, ending the chance of a legacy in the UK.

“I would say he was looking to ignite ‘something’ but he wasn’t entirely sure what that ‘something’ was,” Mr Bhar said. “In many respects he appears to have been disingenuous. But that does not mean he wasn’t significant.

“People learnt from Michael X’s failures and learnt very quickly about what was possible and what was effective for black radicals in Britain.”