What does France’s Macron hope to gain in Hanoi?

Paris: Hanoi has shown diplomatic skill in juggling its partnerships with the US, the EU, China and Russia. The French president aims this week to boost trade ties with Vietnam, but defense is also very high on the agenda.

French President Emmanuel Macron has made Vietnam the first stop in his weeklong tour of Southeast Asia, as he seeks to reinforce the EU’s strategic position in a region already caught up in the US-China rivalry.

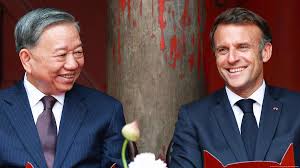

Meeting Vietnam’s top leader To Lam on Monday, Macron was quick to capitalize on the insecurity created by US President Donald Trump’s trade wars and Beijing’s aggressive posturing in the disputed areas of the South China Sea.

“With France, you have a familiar, safe, and reliable friend (…) and in the period we are living in, this alone has great value,” Macron told To Lam, who serves as the secretary general of Vietnam’s Communist Party.

This is the first visit by a French president to Vietnam in nearly a decade.

After Vietnam, Macron will visit Indonesia, where he will meet with Kao Kim Hourn, Secretary-General of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and is also expected to join talks between Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto and Chinese Premier Li Qiang.

He will then travel to Singapore to become the first European leader to deliver the keynote speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue, the region’s premier security forum.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is also expected to visit the region in the coming weeks.

In October 2024, France and Vietnam upgraded their relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, the highest designation for Hanoi’s diplomatic ties, making France — once a colonial power in the region — the only European country to hold this status.

But Hanoi has also signed similar accords with the US, Russia, China, and multiple other nations such as India, Australia and Singapore.

“Vietnam is better than any other country in Southeast Asia at hedging its bets and diversifying its markets, economic and diplomatic partners; France is the key to that strategy in Europe,” Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington, told DW.

In turn, many in the West and elsewhere see Vietnam as an increasingly viable alternative to China in providing cheap labor and access to Asian markets.

Vietnam is the EU’s 17th largest trading partner globally and its largest in Southeast Asia, with trade in goods growing by 13% to reach €67 billion in 2024, according to the European Commission.

On Monday, Macron oversaw the signing of significant economic agreements, including a deal for Vietnam’s low-cost airline VietJet to purchase 20 aircraft from Airbus, a European multinational that supplies about 90% of Vietnam’s fleet, according to aviation analytics firm Cirium.

The move comes despite Washington pressuring Vietnam to rethink deals with European companies in favor of US counterparts.

In April, the US imposed 46% tariffs on Vietnam, though implementation has been postponed until July. At the same time, Vietnam has pledged to significantly reduce tariffs on US imports and agreed to several projects involving companies connected to President Trump, including the fast-tracking of a $1.5 billion golf course that Trump’s family business wants to build outside of Hanoi.

Another promise has been to purchase more US goods. Recent reports suggest Vietnam Airlines may purchase more than 200 planes from the American manufacturer Boeing.

However, European officials have warned Vietnamese counterparts that switching deals from European to American companies could jeopardize relations with the EU.

Khac Giang Nguyen, a visiting fellow at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, told DW that Vietnam sees France as “both as a counterweight to China and a bridge to the European markets, especially important given growing uncertainties around US tariffs.”

“Trade will take center stage [during talks with Macron], but security issues won’t be far behind,” he added. “What I’ll be watching most closely is potential progress on nuclear energy cooperation and defence procurement, as Vietnam looks to reduce its reliance on Russian arms.”

While Russia supplied up to 90% of Vietnam’s armaments up until 2022, when Moscow launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Hanoi is now keen to diversify its security portfolio.

As DW reported last week, Southeast Asia is searching beyond the US and Russia for security partners, with Germany and France stepping up their defense diplomacy.

Macron now has a chance to boost defense relations with Vietnam, which has been locked in a decades-long confrontation with China over disputed territory in the South China Sea.

France has conducted freedom of navigation exercises in the waters and has military bases in the Indo-Pacific region, where it still controls several overseas territories, including Reunion and Mayotte.

In a press conference, Macron said that the partnership with Vietnam “entails a reinforced defence cooperation,” noting that both countries have signed multiple projects on defense and space.

Appearing side by side with Macron, Vietnam’s President Luong Cuong said the defense partnership involves “sharing of information on strategic matters” and cooperation on armaments, cybersecurity and anti-terrorism.

However, as Brussels, Beijing and Washington all compete for greater influence in Southeast Asia, many fear that protecting human rights and democracy is no longer a priority for the region’s international partners.

Ahead of Macron’s arrival, human rights organizations urged him to publicly address Hanoi’s deteriorating human rights situation, which has worsened significantly since the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement was signed in 2021.

“The Vietnamese government’s broad and intense crackdown on freedom of speech and assembly is the opposite of what it pledged to France and the EU,” Benedicte Jeannerod, France director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement.

“The authorities have jailed an increasing number of democracy advocates and dissidents and are resisting reforms needed to comply with their human rights obligations,” she added.

Penelope Faulkner, president of the Vietnam Committee on Human Rights, also said Macron “must not forget France’s founding values, which include human rights.”