Open arms case: Spain should have assigned port, not Italy

Rome: Spain and not Italy should have assigned a port for the Open Arms migrant rescue ship, Palermo judges said in a ruling for which the motivations were filed on June 19.

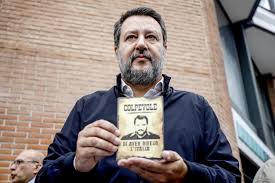

Italy, and thus its interior minister at the time, Matteo Salvini, was not obliged to assign a safe port for the Spanish ship Open Arms when it was carrying about a hundred migrants rescued at sea in August 2019. Spain was instead obliged to do so.

This was the reason for the December decision by Palermo judges to acquit the League party leader of the crimes of neglect of duty and kidnapping for having, illegally, according to the charges, prevented the disembarking of those onboard.

The ruling ended a case that lasted five years, including a three-year-long trial filled with political polemics.

The judicial panel thus ruled that this premise, written in the motivations of the ruling filed on June 19, renders any other defense or accusatory argument useless. The prosecutor had requested a six-year prison sentence for the current deputy prime minister and transport minister.

Salvini commented on the news by saying that “the judges confirmed that defending Italy is not a crime, revealing the stubbornness and the arrogance of Open Arms, which did everything it could to arrive in Italy, discarding all the alternatives that were more logical and natural.”

“The satisfaction over the Palermo judges’ decision does not remove the bitterness for a lengthy trial that cost taxpayers thousands of euros,” he added. “This is the result of the political hatred of the left against me.”

The judges did not discuss defending the country’s borders and focused on the lack of the obligation to assign a safe port as the basis of the acquittal.

The reason for the acquittal is likely to raise debate, especially in light of the decision by the joint sections of Italy’s highest court, which on a similar case — that of the Diciotti ship — recognized the right to compensation for the migrants that had been detained illegally. The prosecution has said that it will decide on a possible appeal after reading the motivations, but it is likely.

“The conviction that in the case in question no obligation to provide a port of safety was on the Italian state, or on the defendant himself,” the prosecutors noted, “clearly exempts the judicial panel from dealing with several issues at an analytical level that had been advanced and hotly debated by the parties.”

Among these issues, they noted, is the “circumstance that the Open Arms ship could serve as a port of safety — that is, the fact that the initial intervention was not in reality a ship in distress, or that the time spent waiting for the port of safety could legitimately be explained with the need to first provide for the distribution of the migrants among European states.”

This conclusion thus goes beyond the defense given by the minister, who never claimed that the assigning of a port was not his responsibility.

According to the court, the obligation to protect the refugees, who were disembarked after a contest of wills and only after Agrigento prosecutors intervened, was Spain’s since its coordination and maritime rescue center had “operated, from the very beginning, a minimum of ‘first contact’.”

Additionally, it added, the responsibility fell on Spain since Malta, “in rejecting its responsibility for the first two rescue incidents, had indicated Spain (the ship was flying its flag) as the only authority that could assist the vessel.”