Are UK interest rates too high?

London: Is the Bank of England policy rate too high? And how fast can the Bank lower it? Costas Milas writes that following Trump’s “stop-go” trade wars, UK interest rates could end up between 0.9 and 1.7 percentage points lower than their current level by mid-2027.

In an interview with The Times, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey suggested that the Bank’s policymakers could proceed with larger interest rate cuts if the jobs market shows signs of a pronounced slowdown. To put that in a context, UK GDP contracted by 0.1 per cent in May 2025, whereas UK inflation rose to 3.6 per cent in June 2025. The average inflation for the second quarter of 2025, therefore, stands at 3.5 per cent, which is slightly above the 3.4 per cent forecast made by the Bank in May.

This should not trouble the Bank’s policymakers materially. All this is happening, of course, at a time of rising international trade tensions fuelled by Donald Trump’s tariff-related “stop-go” policies. Two important questions are looking for answers. First, is the current (in July 2025) Bank Rate of 4.25 per cent too high? Second, how fast can the Bank of England’s policymakers proceed with interest rate cuts?

To answer these questions, I rely on a version of the quantitative model I published (together with my co-authors Michael Ellington and Marcin Michalski) recently. Our model looks at the interactions among the following variables: trade policy uncertainty, UK economic policy uncertainty, UK GDP growth, UK CPI inflation and Bank Rate (the last three variables from the Bank of England’s millennium database extended using recent Office for National Statistics data).

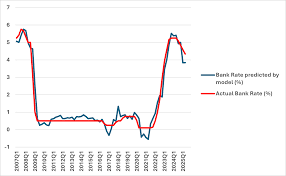

Figure 1 plots what the model thinks about the “appropriate” Bank Rate together with the actual rate decided by the Bank’s policymakers over the 2007-2025 period. I note the following:

The Bank’s policymakers could have cut the rate to negative territory most notably during the recent pandemic period.

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (in February 2022), which triggered a spike in world and UK inflation, Bank Rate could have remained higher at 5.5 per cent in late 2023 rather than hitting a “ceiling” of 5.25 per cent.

The model, which considers the trade wars of Donald Trump and their adverse impact on the UK economy, suggests a Bank Rate of 3.8 per cent in the second quarter of 2025, some 50 basis points lower than the average Bank Rate of 4.33 per cent over the April-June 2025 period. In other words, the model suggests that current monetary policy in the UK is tight and therefore further Bank Rate cuts could be implemented over the rest of 2025.

So how damaging are Trump’s trade wars for the UK economy and how far down can UK interest rates go? To answer this question, Figure 2 looks at the impact of a trade uncertainty shock (one-standard deviation in magnitude) on the rest of UK economic variables over a horizon of eight quarters (two years). Trump’s trade wars increase UK inflation temporarily. From Figure 2, a trade uncertainty shock raises UK inflation by 0.4 percentage points within four quarters. But as the trade shock takes its toll on GDP growth (UK growth drops by 0.6 percentage points within eight quarters), the total effect on inflation turns negative two years from now. The Bank’s policymakers respond by lowering interest rates. Indeed, two years from now, Bank Rate is approximately 1.5 percentage points lower than today.

Using UK economic policy uncertainty in the model above makes sense. This is because Trump’s trade wars make economic conditions much more uncertain and therefore inflict additional damage to the UK economy. This is what we can call “second round” effects from Trump’s trade war via the economic uncertainty “channel”.

Think, for instance, how Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves has responded, so far, to Trump’s wars. Tariff wars have put additional pressure on UK government finances, therefore creating speculation of increased taxes to restore fiscal discipline. This is far from a trivial point to make. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) currently predicts that UK government debt is on its way to hit 270 per cent of GDP by 2070.

In light of Trump’s wars, rising economic policy uncertainty in the UK has materialised in terms of a number of U-turns in economic policy and/or indecisive economic action. One U-turn relates to winter fuel payments for pensioners which Rachel Reeves only recently decided to reinstate. Another U-turn relates to Labour’s welfare reform bill. Additional economic policy uncertainty is caused by speculation of a wealth tax, that is, extra levies on the rich. Needless to say, the Labour government itself has also contributed considerably to rising domestic economic uncertainty over and above Trump’s actions.

But how robust are the above findings to alternative model specifications? I use the UK unemployment rate rather than GDP growth in the empirical model. Unemployment rate is a lagged indicator in the sense that it reacts slowly to economic developments. From Figure 3, UK unemployment rate drops by only 0.1 percentage points within a period of eight quarters. In this case, the Bank Rate is cut by a total of 1.2 percentage points (instead of 1.5 percentage points discussed in Figure 2 above) within eight quarters.

As a further robustness test, I use a measure of UK financial stress conditions (rather than economic policy uncertainty). Financial stress conditions monitor volatility in the sterling exchange rate, as well as volatility in stock and bond markets. Figure 4 suggests similar findings to what we observe in Figure 2. Notice, however, that in Figure 4, Bank Rate is cut by 1.7 percentage points within a period of two years.

As I final robustness test, I have used the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) measure of output gap in my model instead of GDP growth. A positive (negative) output gap value indicates the UK economy over-performs (under-performs) relative to its historical trend. From Figure 5, Bank Rate is cut by a total of 0.9 percentage points within eight quarters.

From the estimates reported above, the Bank of England’s policy interest rate could be cut by between 0.9 percentage points and 1.7 percentage points in total over the next two years. Needless to say, the total cut in Bank Rate is far from certain and different model specifications might give different conclusions. My estimates largely relate to Trump’s tariff wars. One might hopelessly (?) think that tariff-related threats would be abandoned sooner rather than later. Even if this turns out to be the case, the first few months of Donald Trump in office have taught us that the US president will, one way or another, keep producing a number of highly unexpected economic “ideas” that will challenge the international economy and policymakers across the world.